What are metanephrines?

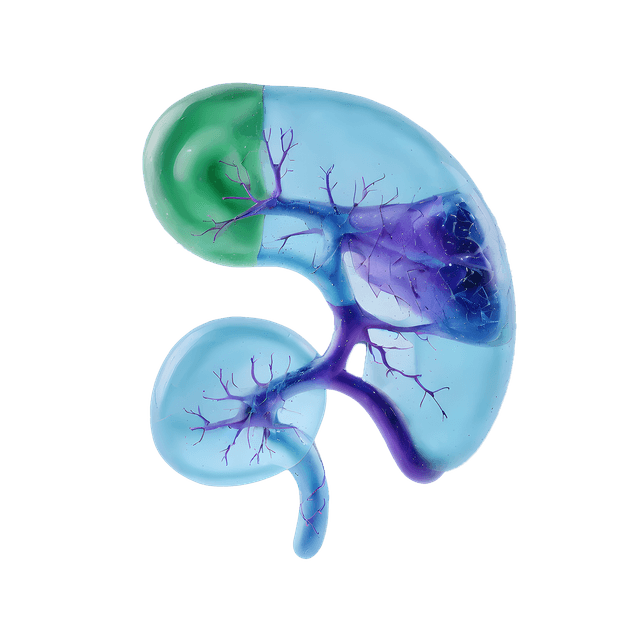

Metanephrines are stable breakdown products (metabolites) of the body's stress hormones known as catecholamines. They are formed when adrenaline, noradrenaline and dopamine are broken down in the body, mainly via the enzyme catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT). Metanephrines circulate more stably in the blood compared to the catecholamines themselves and can therefore be used as a reliable measure of the body's catecholamine production over time.

Analysis of metanephrines is used primarily in the investigation of hormone-producing tumors that can produce stress hormones, mainly pheochromocytoma (tumor in the adrenal medulla) and paraganglioma (tumor in the ganglia of the nervous system). These conditions are relatively uncommon but important to detect because they can cause severe symptoms and sometimes lead to serious complications, especially related to blood pressure and the cardiovascular system.

Unlike direct measurement of adrenaline and noradrenaline, which are often released pulsatilely (in attacks), metanephrines provide a more stable and diagnostically useful picture of whether the stress hormone system is overactive.

The role of metanephrines in the body

Metanephrines have no hormonal effect of their own, but function as biological markers for the activity of the body's stress hormone system. When catecholamines are released – for example, during stress, physical exertion, pain or illness – they are rapidly broken down and converted into more stable metabolites, including metanephrines.

In normal physiology, metanephrine levels reflect balanced activity in the sympathetic nervous system. In certain disease states, however, catecholamine production can become more continuous and uncontrolled, which can lead to elevated metanephrines even at rest

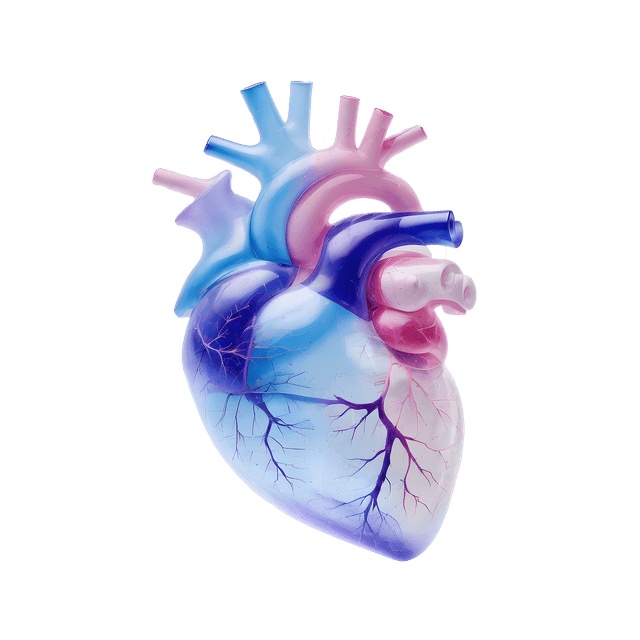

Relationship to catecholamines and adrenal function

Metanephrines are closely linked to adrenal hormone production. The adrenal medulla produces catecholamines as part of the body's acute stress response ("fight-or-flight"). These hormones affect, among other things, blood pressure, heart rate, blood sugar, and blood flow to muscles. After release, catecholamines are rapidly broken down into methoxylated metabolites. In simplified terms, the relationships can be described as follows:

- Adrenaline > methoxyadrenaline (metanephrine).

- Noradrenaline > methoxynoradrenaline (normetanephrine).

- Dopamine > methoxytyramine.

The term metanephrines is often used as a collective name for these breakdown products and provides an overall picture of catecholamine metabolism in the body.

Symptoms of elevated levels of metanephrines

Elevated levels of metanephrines are not a disease in themselves, but a signal of increased catecholamine production. It can give rise to symptoms that often come in attacks and can vary in intensity:

- Sudden or difficult-to-treat high blood pressure.

- Palpitation or rapid pulse.

- Heavy sweating.

- Headache.

- Internal stress, worry, anxiety or tremor.

- Palour, nausea or weight loss.

Because the symptoms can be intermittent, the condition can sometimes be difficult to detect without targeted sampling.

Why is metanephrine analyzed?

Analysis of metanephrines is a central part of the investigation when pheochromocytoma or paraganglioma is suspected. The test may be relevant for:

- Investigation of unexplained or difficult-to-control high blood pressure.

- Recurrent attacks with typical stress hormone symptoms.

- Suspected hormone-producing tumor based on clinical presentation.

- Hereditary pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma or genetic syndromes (e.g. MEN2, VHL, SDHx).

- Follow-up after treatment or surgery.

Normal levels of metanephrines strongly suggest pheochromocytoma, especially if the sample is taken under correct and calm conditions.

Metanephrines can be analyzed in free plasma or in urine. Plasma analysis has very high sensitivity and is often used as the first choice in cases of suspicion. Since stress, body position, caffeine, nicotine, physical activity and certain medications can affect the result, correct sampling is important to reduce the risk of falsely elevated values. Elevated values do not automatically mean diagnosis, but should always be assessed by a doctor and, if necessary, followed up with further investigation, such as additional laboratory tests and/or imaging. The result should always be interpreted in relation to symptoms and the overall clinical picture.