Quick version

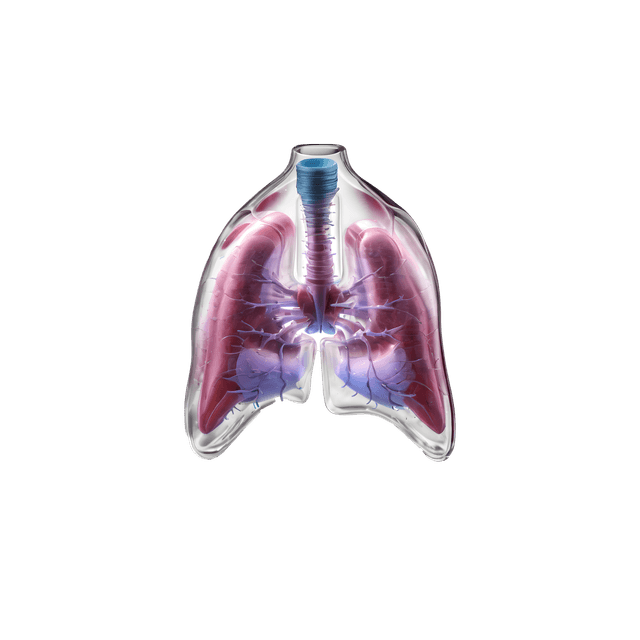

Thalassemia is an inherited blood disorder that affects how the body forms hemoglobin – the protein in red blood cells that transports oxygen. When hemoglobin does not function optimally, you can develop anemia and symptoms such as prolonged fatigue, decreased energy, pallor, palpitations and shortness of breath on exertion. Many with mild thalassemia (carrier status/thalassemia minor) have few or no symptoms and are only diagnosed when a blood test shows abnormal values.

In Sweden, thalassemia is relatively uncommon, but occurs regularly and is well known in healthcare – especially in people originating from regions where the condition is more common. Since thalassemia often causes low MCV and low MCH, it can resemble iron deficiency. Therefore, iron deficiency almost always needs to be ruled out first with an iron test (e.g. ferritin, transferrin and iron saturation), before proceeding with hemoglobin typing (Hb electrophoresis) and sometimes genetic analysis.

Treatment depends on the type and severity. Mild thalassemia usually requires no treatment, while more severe forms may require transfusions and follow-up with a hematologist.

Although thalassemia is sometimes described as uncommon, globally it is one of the world's most common genetic diseases. In Sweden it is less common, but occurs regularly and is well known in healthcare.

Because the condition often causes low MCV and low MCH, it can resemble iron deficiency, which sometimes delays diagnosis. Many people are told they have "low blood counts" without the underlying cause being investigated further. Distinguishing between iron deficiency and thalassemia is therefore an important part of a correct blood test.

The symptoms vary greatly depending on which form of thalassemia you have. Some live completely without any problems, while others can develop more pronounced anemia and in some cases complications over time.

What is thalassemia?

Thalassemia means that the production of hemoglobin is reduced or incorrect. This leads to the red blood cells becoming smaller and more fragile, which impairs oxygen transport in the body. Thalassemia is a genetic disease, which means that you are born with the condition and cannot develop it later in life.

The impaired oxygen transport can give rise to the following consequences:

- Anemia.

- Chronic fatigue.

- Reduced physical strength and endurance.

- Paludability

- Palpitation

- Shortness of breath on exertion

How common is thalassemia?

Thalassemia is one of the world's most common hereditary blood diseases, but in Sweden it is considerably more uncommon. The incidence is higher in parts of the Mediterranean region, the Middle East, Africa and Southeast Asia. In Sweden, thalassemia is primarily seen in people originating from these regions, but the condition occurs regularly and is well known within Swedish healthcare.

Even mild forms, called carrier status (thalassemia minor), are relatively common globally and can sometimes be discovered by chance during a blood test.

Thalassemia occurs in different types based on the effect on hemoglobin

Thalassemia is divided into alpha and beta thalassemia depending on which part of the hemoglobin is affected. Both forms can vary from mild to severe.

Beta thalassemia is most often divided into:

- Minor (carrier status) – usually mild or without symptoms.

- Intermediate – moderate anemia.

- Major – severe form that often requires regular blood transfusions.

Alpha thalassemia also varies in severity from mild anemia to more severe forms.

Diffuse symptoms can make thalassemia difficult to detect

Because the symptoms often resemble iron deficiency or stress-related fatigue, thalassemia can remain undetected for a long time. Many people are repeatedly told that they have "low blood counts" without further investigation of the underlying cause.

Common signs may include:

- Long-term fatigue that does not improve despite rest.

- Reduced energy during exercise or physical exertion.

- Pale skin or pale mucous membranes.

- Shortness of breath faster than expected.

- Palpitation with mild exertion.

- Dizziness, headache or difficulty concentrating.

If you have prolonged fatigue combined with low MCV or unexplained anemia, it may be justified to investigate the cause further, the first natural step is to check your iron levels and your blood status.

How is thalassemia detected?

Thalassemia is most often detected via blood tests, where typical changes in blood status are seen. Many people are diagnosed in connection with investigating prolonged fatigue or low blood values.

Common findings in blood status are:

- Low hemoglobin (Hb).

- Low MCV (small red blood cells).

- Low MCH.

- Sometimes normal or high red blood cell count despite low Hb.

Since iron deficiency is a much more common cause of low MCV, this always needs to be ruled out first. An iron test usually includes ferritin, transferrin and iron saturation. You can read more about how such an examination is done in our iron deficiency test.

Further examination may include:

- Hb electrophoresis (hemoglobin typing).

- Extended iron status.

- In some cases genetic analysis.

How is thalassemia treated?

The treatment of thalassemia depends on the type and severity of the condition. In mild forms, such as thalassemia minor, active treatment is usually not needed. The most important thing is that the diagnosis is made correctly so that the condition is not confused with iron deficiency and treated with unnecessary iron supplements. Many people with mild thalassemia live without symptoms and only need follow-up when necessary.

In more severe forms, anemia may be more noticeable and require medical treatment. This may involve regular blood transfusions to maintain a sufficient hemoglobin level. Since repeated transfusions can lead to iron accumulation in the body, iron chelation therapy is sometimes needed – a drug that binds excess iron so that it can be excreted. Some patients may also be recommended folic acid supplements, and follow-up is usually done by a hematology specialist.

Can iron be reduced with diet or supplements?

The composition of the diet can affect how much iron is absorbed from the intestine, but it is important to have realistic expectations. The body cannot break down or actively eliminate excess iron to any great extent on its own. Therefore, in cases of documented iron excess, dietary changes or supplements are not sufficient as treatment.

If iron levels are elevated, medical treatment and follow-up within the healthcare system are usually required. Dietary advice can be a complement, but does not replace established treatment for iron overload.